By SGN | 12 Feb 2026

Witnessing dementia firsthand

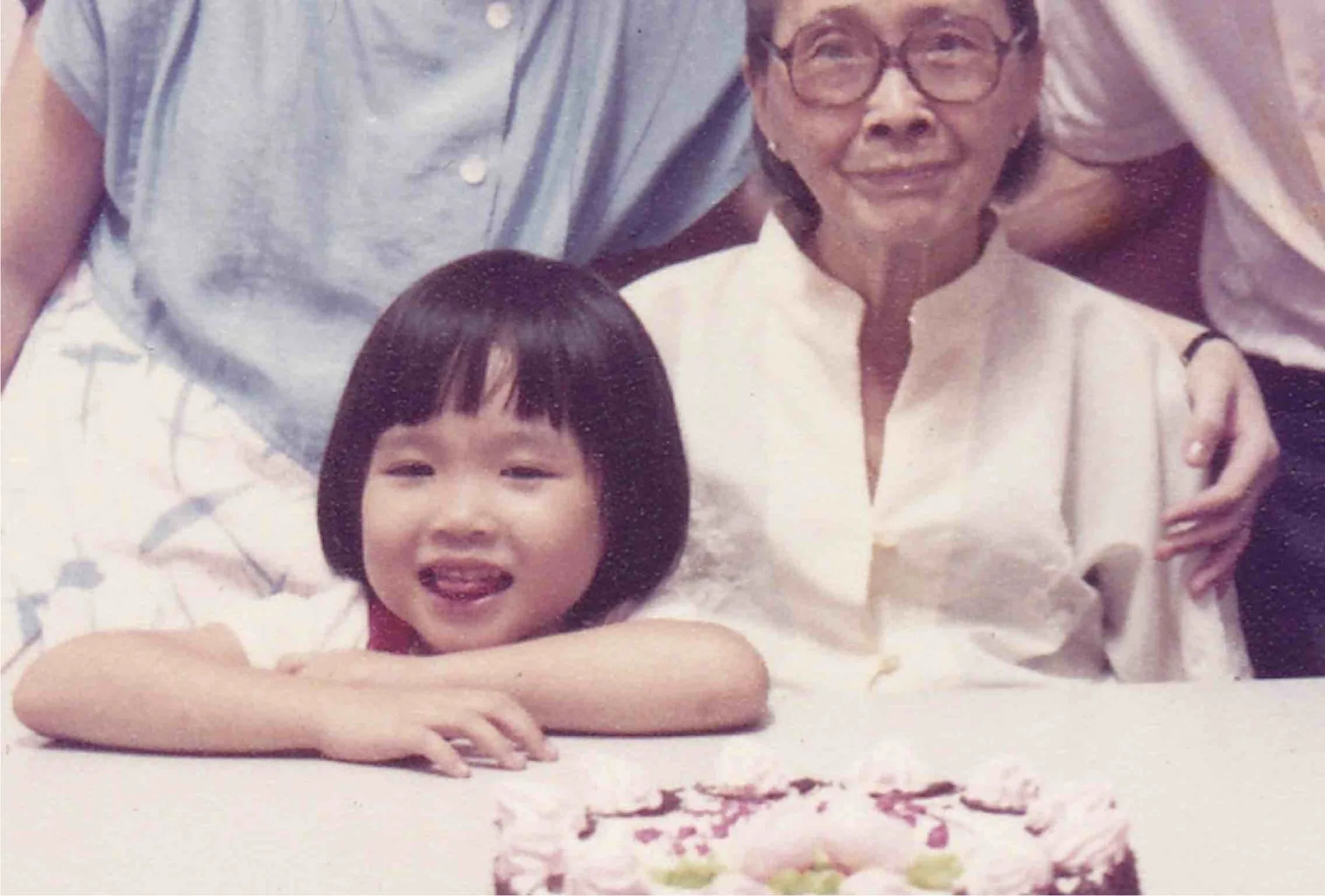

Joanna recalls the story of her great-grandmother, affectionately known as lau ma.

In the final years of her life, lau ma began to slip away, her mind clouded by what was understood to be dementia associated with ageing.

At the time, there were few words to explain what was happening. People’s knowledge and understanding of dementia was shrouded in superstition, misinformation, and half-truths.

“I was told that dementia was similar to an old car disintegrating after years of use,” she says.

Over time, Joanna stared noticing that something wasn’t quite right with lau ma. “She’d wear the same clothes for days. We’d tell her to shower, and go through her wardrobe to select new clothes for her to wear,” she recalls.

As lau ma’s dementia progressed, other family members’ concerns about her behaviour escalated. Her primary caregivers decided to renovate her house entirely. The metal grills, tiled floors, and hardwood furniture she’d known her entire life would be removed to make space for a modern, resort-style interior.

“Lau ma had lived in that house for forty years,” Joanna recounts. “So, imagine her confusion when she returned after time away, to find that the house she had known her entire life was fundamentally altered.”

Lau ma did not take well to her new surroundings. When she looked out of the window of her house, everything looked the same: the handrails, pavements, and paths had not changed one bit. But the inside of her home was no longer something she recognised. At night, her confusion and anxiety over her new surroundings were heightened.

Eventually, lau ma’s discomfort at the drastic alteration of her space bled out into the rest of the family.

“The memory of waking up at two in the morning and watching my parents depart to deescalate the situation next door stayed with me,” she says.

This memory was pivotal to Joanna’s decision to pursue a lifelong career in dementia research.

Starting afresh in Australia

“I have a cheesy story as to how my life in Australia started.”

After graduating from university in Singapore, Joanna decided to go on a holiday. “Fuelled by the invincibility of youth, I quit my job, and decided to head to Australia based on a friend’s recommendation,” she shares.

At first, she considered opting for the well-worn route of visiting Melbourne. But her friend suggested she visit Tasmania as well. “I was told that it was a beautiful place, located right at the bottom of the world,” she chuckles.

This friend had connected her to her now husband, Simon.

“Simon drove me around all the breathtakingly beautiful places in Hobart, and we got close over chats that took place during our long drives,” she recalls.

The rest is history. Simon saved up money to visit her parents in Singapore, who later gave the couple their blessing to get married. “I had some savings, so I thought I’d settle down in Tasmania and give it a go,” she says.

Joanna marvelled at how empty the streets in Tasmania were, especially on weekends, early store closures, and how clearly she could see the night sky.

“After I moved to Australia, I realised I could finally see the stars at night,” she shares. “There were no lamp posts or streetlights, and whenever we looked up at the night sky, we could see dozens of twinkling stars.”

Finding community proved to be a breeze for the chatty Joanna, who was unafraid of striking up conversations with strangers.

“Singaporeans are adaptable people, so we just jump into new situations,” she says, having found her community in Simon’s friends and family, and also in some members of her former alma mater.

“There are a lot of Singaporeans speckled all over the world. Most I met in Tasmania were women, so it feels like a sisterhood,” she says.

Joanna officially moved to Tasmania in 2006, then Singapore and back again in 2013. She, along with Simon and their two children, having been living there ever since.

Building a career in dementia research and gerontology

Despite possessing a degree in psychology, Joanna had trouble securing a job in Tasmania.

So, she decided to enrol in an Enrolled Nursing course (equivalent to a diploma in Nursing), and ended up working as a personal care assistant in an aged care facility.

This would be her first encounter with people living with dementia in a residential nursing home setting in another country. What she witnessed was a stark contrast to the “a quiet patient is a good patient” attitudes she was accustomed to in Singapore.

“In the past, Singapore’s system took a more clinical approach with a perspective of safety. We were always told that this person needs to stay at home, and do nothing,” she reveals.

A term for this phenomenon has been coined by Kate Swaffer, an Australian activist for the rights of people with dementia, known as “prescribed disengagement”.

“As a person living with dementia, you are told to disengage with all facets of your life, because doing so would be too dangerous for you cognitively,” she says. “You’re told to stay at home and watch television.”

In contrast, Australia’s approach to dementia care proved to be a change for Joanna, who found her experience at Vaucluse Gardens Residential Care Home to be eye-opening.

She witnessed firsthand how the residents continued to live full lives, despite grappling with dementia. “People were engaged in all sorts of activities, and going for excursions,” she shares. “Their lives did not pause just because they were diagnosed with this syndrome.

Inspired by her experiences in Australia, she wondered if she could carry on this line of work in her native Singapore.

In 2011, when she returned to the country, she came across an opportunity with the Agency of Integrated Care (AIC), which required the candidate to be well-versed in dementia care.

In her role as Programme Manager, Joanna was tasked with building dementia care initiatives from the ground up.

Rather than diving into policy, she began by listening. She spoke extensively with volunteers working alongside people with dementia and their families in public housing estates across Singapore.

These conversations revealed to Joanna what she already knew from firsthand experience: the most ideal place for people with dementia to live and recuperate was a familiar one.

“The best place to be is home,” she says.

“When people are moved into nursing homes or other secondary locations, there is a deep, unspoken grief that often accompanies this transition.

“Imagine how you’d feel when everything that you have known for the last forty or fifty years is either discarded or compressed into a tiny suitcase.”

Yet when people with dementia are compelled to remain indoors or are prevented from moving freely without explanation, confusion and distress often follow.

“For example, if your loved one with dementia wants to go outside for a walk but sees that the front door or gate is padlocked without any explanation, they will become agitated,” she explains.

“Usually because no one explains why they cannot go out. They may deduce that someone is keeping them in, and they are doing so while they are already experiencing cognitive deterioration.”

Once an outburst occurs, the impact ripples outward.

“Everyone becomes stressed,” she says. “People’s ability to rationalise is compromised, and their fear response is at an all-time high. Which is why we need to work together to help everyone to understand what’s happening, so things are easier for everyone involved.”

These conversations sharpened Joanna’s resolve. The problem, she realised, was not only clinical. It was social, environmental, and intertwined with public misunderstanding.

If people living with dementia were being hidden away, then awareness, design, and access needed to change.

Creating meaningful resources for the dementia inclusive communities

In 2014, Joanna joined the Wicking Dementia Centre as a Project Officer. Over the years, she gradually worked her way up through the organisation, and is now a full-time lecturer, shaping how dementia care is taught and understood.

But Joanna wanted more than institutional change. She wanted tools that could shift practice on the ground.

That impulse led her to pursue a PhD at the University of Wollongong, where she began developing the Singapore Environmental Assessment Tool (SEAT), a culturally responsive framework designed to evaluate how built environments in Singapore’s aged care facilities support people living with dementia.

From the outset, SEAT was built collaboratively.

Working with the Agency for Integrated Care and multiple nursing homes in Singapore, Joanna spent the first two years of her thesis interviewing nurses, healthcare workers, administrators, operations staff, and caregivers to better understand how people with dementia experienced Singapore’s aged care facilities.

What she heard challenged imported ideas of “good” dementia design. Stakeholders emphasised the need for spaces that felt unmistakably local: nursing homes that resembled HDB flats, avoided culturally inauspicious colours like black, included prayer rooms, and offered strong WiFi connectivity.

“I’ve seen seniors with dementia own as many as four smartphones,” she chuckles.

These findings stood in contrast to Australian dementia-friendly environments, where design often prioritises access to nature.”

In contrast, dementia-inclusive spaces in Australia look a little different. “In Singapore, people rejoice when they can see the sky from their HDB balconies,” she explains. Meanwhile in Tasmania, people want to look outside their windows and see streams and creeks,” she shares.

SEAT was launched in 2021, to considerable fanfare from the dementia care community in Singapore. “With a tool like SEAT, healthcare professionals, architects and policymakers in Singapore can make better design decisions for people living with dementia,” she shares.

Yet for Joanna, research alone was not enough.

Through her teaching and engagements with universities and nursing faculties, she noticed how difficult it was for practitioners, caregivers, and family members of people with dementia to access practical, evidence-based guidance on dementia-inclusive environments. Much of the knowledge remained siloed within academic institutions.

Deciding to take matters into her own hands, Joanna created the Design and Dementia Global Knowledge Translation Project (DESIGN), an open-access resource hub that translates research into usable, real-world tools.

The platform brings together best practices, research findings, podcasts, infographics, and blogs, resources often locked behind paywalls or confined to classrooms.

So far, the reception to her work has been overwhelmingly positive, both in Australia, and back home in native Singapore.

“People have told me how they find the hub useful, because this information would otherwise have been gatekept behind courses worth hundreds of dollars, or only taught in classrooms,” she reveals.

To ensure the project stays relevant for its intended audience, Joanna regularly works with people living with dementia, gathering crucial feedback and insight.

Crucially, the project is shaped in constant dialogue with people living with dementia. Joanna regularly gathers their feedback, refining not just what information is shared, but how it is written and presented.

“We can’t create resources for people without involving the people most likely to use them,” she says. “This feedback is what keeps the work honest and relevant.

Singapore’s changing dementia care landscape

Over the years, the tireless advocacy work of people with dementia and their allies have gradually brought about a change in societal attitudes, especially in Singapore.

“In the last decade, Singapore has progressed leaps and bounds when it comes to dementia care,” she shares.

This is evident in the country’s architectural design. Dementia-inclusive residential estates like Nee Soon, Yio Chu Kang, Marine Parade, and Kebun Bahru stand out for their wayfinding signages, designed to help people with dementia navigate the neighbourhood, and unique murals reminiscent of traditional snacks instantly recognisable by older people, like ang ku kueh.

Features like these represent yet another step towards a Singapore designed keeping in mind those with dementia and other neuro-degenerative diseases.

But there is room for more action, and Joanna is acutely aware of this.

“Progress lies in all the little actions and adjustments,” she shares. “The greater awareness there is of dementia and its related challenges, the more inclusive can our society be.”

For Joanna, dementia-inclusive design is not a niche concern, but a societal one.

“When people with dementia can age in peace, and within a thriving community that upholds and support them, everyone benefits. Families are less overwhelmed, and the pressure on hospitals is eased. Dementia-inclusive design isn’t just about individual care, it’s about creating sustainable communities that work better for everyone.”

About Joanna

Dr Joanna Sun is a gerontologist and lecturer at the Wicking Dementia Research Centre. With over two decades of experience in the dementia care industry in both Singapore and Australia, Dr Sun’s research focuses on developing enabling and inclusive environments for people with dementia.

Connect with her here.